In the UK, someone is diagnosed with cancer every two minutes, and some types remain harder to tackle than others. Our researchers are working to understand why some cancers are resistant to treatment, and developing novel approaches to overcome this challenge.

Strengthening antibodies

Professor Mark Cragg has been exploring different ways of using antibodies - a key part of the body's own immune system - to track down and treat cancer in the same way they already do for bacteria and viruses.

In particular, Mark and his colleagues are trying to understand why some patients respond well to immunotherapy and move towards long-term survival, while others either don't respond, or do at first before becoming resistant.

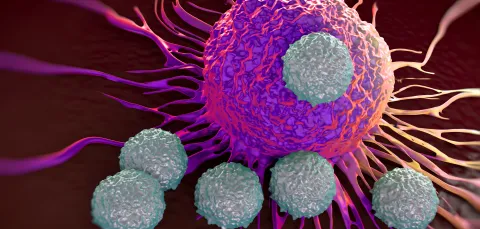

During immunotherapy, antibodies will bind a tumour cell to a macrophage - white blood cells which digest harmful cells - causing the macrophage to 'eat' the cancer cell. However, when tumours grow, they attract and change the behaviour of normal cells surrounding them, to form what is called a tumour microenvironment.

Sometimes a tumour alters macrophage cells so that the antibodies can't activate them, which protects it from the body's immune system. The degree to which this can happen varies in each person, which explains why some people respond better to treatment than others.

Mark's research is working to reverse the tumour cell's defence against macrophages, by reactivating them so they can continue to fight it.

"For us, the next step is developing a deeper understanding how cancer cells manipulate the immune system to avoid destruction, and then designing ways of stopping them."

Professor Mark Cragg

Understanding fibroblasts

There is another type of cell that can also cause resistance to cancer treatment: fibroblasts. Gareth Thomas, a professor of experimental pathology who specialises in head and neck cancers, has been focusing on these cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF).

In a healthy body, fibroblasts provide the scaffolding for normal tissues, but they can be hijacked by cancer cells to become CAF. In a recent paper published by Gareth and his team, they uncovered that cancers which contain lots of CAF behave very aggressively, and that the most hard-to-treat cancers contain lots of these cells.

Gareth's team have been trying to understand how CAF hide cancers from the immune system. Working with groups in engineering allows them to look at this more closely, using imaging technology to map the structure of patients' cancers.

Their aim is to find ways of targeting CAF, such as by tackling an enzyme called NOX4 which seems to be important in activating CAF in most cancer types. Early experiments show that an existing drug, which is already used to treat organ fibrosis, may hold the key to improving response to immunotherapy by blocking NOX4.

"As we understand more about tumour biology, the way we classify and treat cancers will change, and therapy will become much more personalised to the individual patient, rather than being based on cancer type," says Gareth.

Cancer classification and collaboration

Mark, Gareth and many other researchers are working together with clinicians, scientists and surgeons, both in Southampton and around the world, to solve these problems. This collaboration of expertise ensures that teams can fight cancer more effectively, working to make treatment resistant cancers a thing of the past.

Our Centre for Cancer Immunology is the first in the UK to bring these specialists together under one roof to focus uniquely on this kind of research.