Overview of a Simple ARM SoC

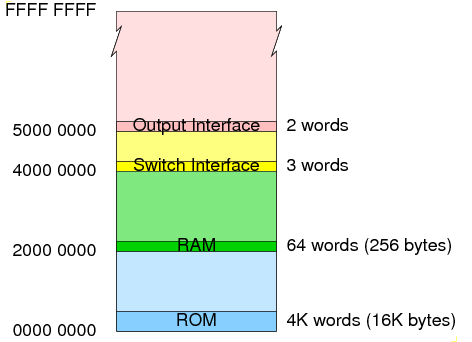

A very simple ARM System on Chip has been designed:

- ROM

16K bytes for program memory - RAM

256 bytes for data memory (including stack) - Switch Interface

Occupying three 32-bit memory locations - Output Interface

Occupying two 32-bit memory locations

Memory Map

-

The memory map is sparsely populated with the unused areas being filled with secondary images

of the real slave devices:

The secondary images are an artefact of the partial address decoding which only uses the top 4 address bits (HADDR[31:28]) in order to decide which slave is being accessed.

Files

In order to build the ARM SoC, we need SystemVerilog files to model the hardware plus 'C' program files and other support files to build the software. Further files are required to support simulation:

- Hardware

- Software

- C Program Code

- Support files

- Simulation

Operation of the custom interface modules

SoC design is a blend of hardware design and software design including third-party components such as microprocessor cores and library software and custom components such as custom interfaces and application software. When looking at the custom components, there is often a trade-off to be made between undertaking a particular task in hardware or software. Some tasks may be easily carried out in hardware leading to simplified software while other tasks may be more easily carried out in software leading to simplified hardware.

In this example we have two custom interface modules which have been designed to integrate with the external world (in this case just switches, buttons and LEDs) and simplify the software:

- Switch Interface

The switch interface (ahb_switches.sv) allows numbers to be entered via 16 switches and two buttons.

In order to enter a number, the user will set up the binary number on the switches and then press one of the buttons.

The aim of the interface is to avoid the processing of unwanted/false data - for example, changing the switch input from 3 to 4 may involve the following transitions:

0000 0000 0000 0011 (3) 0000 0000 0000 0111 (7) 0000 0000 0000 0101 (5) 0000 0000 0000 0100 (4)

including two unwanted/false data values (7 and 5).By introducing a button for number entry, we can ensure that only valid numbers are entered. By introducing a second button it allows us to enter two different 16 bit numbers using only 16 switches.

Based on this requirement, we might design an interface containing two registers:

- SwitchData[0] Register containing 16 bits from switches entered via Button[0]

- SwitchData[1] Register containing 16 bits from switches entered via Button[1]

In this case we would have no way to distinguish a series of numbers: 5,7,3 entered via Button[0] from a longer sequence including repeats: 5,7,7,7,3,3.

The more sophisticated approach used here includes a third register containing status information combined with a handshaking protocol which is typical of a lot of custom interface harware:

- When one of the buttons is pressed, the relevant SwitchData register is updated and the associated bit in the Status register goes to 1.

- When one of the SwitchData registers is accessed by the processor, the associated bit in the Status register goes to 0.

This allows the processor to see if there is new data available, simply by checking one of the bits in the Status register.

Note that this interface does not deal with switch bounce. If switch bounce is perceived to be a problem, we could include software which might ignore duplicate data entered in quick succession. Alternatively debouncing hardware could be added to the switch interface.

- Output Interface

The output interface (ahb_out.sv) allows data values and error status (data validity) information to be displayed via LEDs.

The aim of the interface is to ensure that the data and the data validity information is always in sync.

Based on this requirement, we might design an interface containing two registers:

- DataOut Register containing 32 bits of data

- DataValid Register containing a single data bit telling us whether the data is valid

With this simple approach we have a problem that, whichever register is updated first, we will have a few clock cycles where the DataValid value doesn't correspond to the DataOut value (e.g. if the DataOut register is updated first, there will be a few cycles when the old DataValid value and the new DataOut value exist together). While this is not a problem if the output is going to some LEDs it will often cause a problem if the output is driving some other circuit. For this reason this interface is designed such that DataOut and DataValid change on the same rising clock edge.

To support this operation, we will have two addressable registers (these are the registers that are visible to the programmer):

- DataOut Register containing 32 bits of data

- NextDataValid Register containing a single data bit telling us whether the next data is valid

and a third register which is not addressable:

- DataValid Register containing a single data bit telling us whether the data is valid

In order to output a data value, the programmer will write a bit to the NextDataValid register to specify the vailidity of the next data and then write the data itself to the DataOut register. The writing of the DataOut register will trigger a copy of the NextDataValid register to the DataValid register thus ensuring that the two outputs are always in sync:

DataOut <= HWDATA; DataValid <= NextDataValid;In common with many custom interface circuits, this interface also supports a Status register which allows the programmer to see the current status of both the DataValid and NextDataValid bits.

- Register Access Quirks

The memory-mapped registers in these custom interface circuits have a variety of features:

- Read/Write Registers

The DataOut register in the output interface can be read or written.

- Read-Only Registers

The SwitchData registers in the input interface can be read but not written. The same goes for the Status registers in either interface.

- Write-Only Registers

The NextDataValid register in the output interface can be written but not read.

- Register Access Side Effects

Writing to the DataOut register in the output interface has the side effect of changing the DataValid register and the Status register. Similarly reading from a SwitchData register in the input interface has the side effect of changing Status register.

When you design your own custom interface circuits you should think about the access requirements and access side effects for the memory-mapped registers.

- Read/Write Registers

Preparation

- Create a new directory for the lab (e.g. ~/design/system_on_chip/example_arm_asic)

and change to the new directory:

mkdir -p ~/design/system_on_chip/example_arm_asic cd ~/design/system_on_chip/example_arm_asic - Copy the design files (not including the Cortex-M0):

init_arm_soc_asic_example -here - Download the obfuscated Cortex-M0 file and place it in the behavioural subdirectory:

Compile C Program

- In the software sub-directory, the

makefile and the

soc.ld linker script

are used to compile the main C language file:

main.c,

and the support files:

vectors_designstart.c and

crt.c.

Running the appropriate make commands in the software directory:

cd software make clean make code.vmemshould create a Verilog hex format file named "code.hex" which could be used in simulation but not in ASIC synthesis and a "code.vmem" version of the same hex data which is better suited to ASIC synthesis. - Open the "code.hex" and "code.vmem" files in a text editor to check that they have been created.

- Run an additional make command to create a dissassembly listing of the program:

make code.lstExamining the "code.lst" file in a text editor can be very helpful when trying to debug a system-on-chip design in simulation.Note that you can generate "code.hex", "code.vmem" and "code.lst" files at the same time using the following make command:

make all

Simulate ARM SoC

- In the main directory (~/design/system_on_chip/example), a

simulate script exists to

simplify the task of running the simulation:

cd .. ./simulate &(The xmverilog command to run the simulation is:

xmverilog +gui +access+r \ +tcl+testbench/soc.tcl \ -y behavioural +libext+.sv \ +define+prog_file_vmem=software/code.vmem \ testbench/soc_stim.svbut it's easier to use the simulate script) - Consult the HADDR and HSEL_... signals in the waveform window and satisfy yourself that the correct active HSEL_... signal is being selected based on any particular address value. (Identify at least one address for each of the HSEL_... signals and confirm that it is in the correct range)

- Look at the Console output and the main.c program. Can you explain the sequence of "DataOut" values that you see in simulator console?

- Add the contents of the RAM to a memory viewer window and work out how much of the RAM is in use with this program. (You will have to 'rewind' and re-run the simulation in order to see

the contents of the RAM).

You are looking for three regions:

- Global data (lower memory addresses)

- Unused memory (a region of XXXXXXXX locations between the global data and the stack)

- Stack data (higher memory addresses)

Note that because the stack grows downwards, the higher memory addresses are used before the lower ones.

Although the stack may be sparsely used (there are likely to be unused XXXXXXXX locations in the stack), it should still be possible to identify the larger area of unused memory between the globals and the stack.

Change the program

The following actions should be possible without closing the simulation.

-

In the software/code/main.c file, replace this line:

if ( switch_temp < 8 ) {(which limits the range of number for which a factorial is calculated) with this line:if ( switch_temp < 16 ) {and re-run the make all command. - Now use the

Simulation -> Reinvoke Simulator...dialogue to re-run the simulation using the newly updated code.hex file. - Is the system able to calculate the factorial of 15?

- Look again to see how much RAM is being used.

- Talk to someone helping in the lab about what has gone wrong.

Change the amount of RAM

- Increase the amount of RAM to 1024 bytes (256 32-bit words) either by editing the behavioural/ahb_ram.sv or the behavioural/soc.sv file.

- Re-run the simulation and confirm that you can see the increased memory size. (You will most likely have to remove the memory from the memory viewer window and then add it again in order to see all 1024 words of memory).

- Has the behaviour of the simulation changed?.

Update the linker script

-

In the software/soc.ld file, replace this line:

RAM (rwx) : ORIGIN = 0x20000000, LENGTH = 256

(which tells the linker how much memory is provided) with this line:

RAM (rwx) : ORIGIN = 0x20000000, LENGTH = 1024

-

Before recompiling you should clean the software directory

to ensure that a new version of code.vmem is generated:

make clean make all

- Now re-invoke the simulator.

- Has the behaviour of the simulation changed?.

- Check with the aid of a calculator to see if the result given by each of the factorial calculations is correct?

At this stage you can experiment with other changes to the system but you should try to make only small changes between simulations to increase the chances of being able to debug the system.

Iain McNally

28-1-2025